The 3 ways I've tried to land a design system into existing software

A success, a partial success and a failure in systems strategy

Hey friends 👋 Welcome back! If you’re new here my name’s Pat. I’m a principal product designer in tech and in this newsletter I explore strategies and tactics from my decade in the business to help you elevate your craft and make what you’re making better... by design.

Today we’ll explore the strategies I’ve tried for establishing design systems in existing products at three high-growth tech companies.

Each team used a different strategy for executing the new design vision. While none is 100% right or wrong, they all have trade-offs which I’ll dig into so that hopefully you can avoid my mistakes!

Let’s go!

The “blow-it-up” strategy

What is it?

You know this strategy. It’s the classic “redesign” project.

In some ways it’s the bread and butter of waterfall style design and development: “old design isn’t working? Let’s come up with a whole new one all at once!” You try to install an entire system via a reimagined product in one fell swoop.

You get to “flip the switch” to a new experience which can feel awesome but you take on a big burden and a lot of risk in pursuit of that wow factor.

What do I think about it?

I’ll be upfront: I think this is a bad idea for software. It’s just a bad match for the medium.

Design is very good at big, wholesale change. Software is very bad at it.

From a design standpoint “blowing it up” is comfortable because it gives a level of perceived creative freedom that people like when making something new. There’s also real merit in being able to step back and design holistically so that you can get the big picture you need to inform how system elements should work in harmony.

From an implementation standpoint “blowing it up” is a nightmare. It’s very complex and introduces many dependencies which ramp up the risk. Not only are you trying to design and architect a new experience from scratch, you’re also trying to make sure that it matches all the existing feature functionality of the old version. There are just too many moving pieces.

The experience you’re trying to replace was likely built iteratively over time. Even with the benefit of seeing its current state, the process of re-architecting every feature is lengthy and error prone. The scope is enormous, which makes this strategy unappealing in all but the most drastic of circumstances.

Due to it’s high complexity and extended time-frame, it’s also very possible this strategy gets terminated part way through. This can leave your new experience worse off than the original or just feel like a colossal waste of time.

How did this manifest in my career?

In my experience this often manifests when a change occurs in product leadership. People tend to exaggerate the flaws of software they inherit because it’s not something they personally made. It doesn’t reflect their decision-making so the easy, knee-jerk reaction is often to blow it up and “do it their way”.

This is the strategy that my team took at Tenable. We did some very cool design work, but ultimately failed to deliver on the vision. The experience we designed was Dribbble-worthy, but neither pragmatic nor feasible given our real world constraints. The project got mostly scrapped after a year of hard work and the experience we shipped was, in my opinion, worse than the original. At best it was a far cry from the “visionary” design we set out to achieve. Also in the process of this slow breakdown, the head of product design got removed from his position and then the chief product officer followed suit.

Verdict: Not exactly what I’d call a success. Would not recommend. 👎

The “Ship of Theseus” strategy

What is it?

The “Ship of Theseus” strategy is the yang to the “Blow it up” yin. For context, here’s the first line of the Wikipedia entry:

The Ship of Theseus is a thought experiment about whether an object that has had all of its components replaced remains fundamentally the same object.

In the case of the namesake, greek legend Theseus, the story goes that over time he replaced every piece of his ship with a new version. So, after swapping out every board, sail and so on for a different one, the question was: is it same ship?

A team following the “Ship of Theseus” strategy would not attempt a wholesale redesign but instead attempt consistent, specific replacements over time. Their goal is to morph the existing experience into something entirely new by swapping all the component pieces for a new version.

What do I think about it?

It’s a safer strategy than “blow it up” but it’s also very tough, just for different reasons. It’s more aligned with best practices for iterative software delivery, but due to how incremental it is it’s harder to use it to set up significant design breakthroughs.

Perhaps the biggest issue is that the level of effort for this strategy depends a lot on how systematized your design already is. Good luck trying to swap every instance of a low level component if you don’t already have a somewhat centralized way to do so. Just like “blowing it up” it’ll still be very error prone and take an eternity.

Another potential issue arises when the new design vision represents a significant aesthetic departure from what exists. In that case you have two options:

You accept that your new elements may feel out of place in the platform for a while until you can get a critical mass of design updated.

You have to dial back your desired aesthetic changes so that they fit better within the bounds of the existing product.

Neither option feels that satisfying for the team despite the technical improvements you might achieve. You’re like “great, we updated all our buttons to be on the system!”… but overall the product feels substantially the same as before which in this context feels like a let down.

Ultimately this strategy can lead the team to feeling like they’re walking in quicksand making little visible progress for their effort. So even though it feels safer at the start, it’s easier for motivation to wane over time and for this kind of project to also get abandoned part way through.

How did it manifest in my career?

This is the strategy my team took at Signal Sciences.

It was mostly successful, but the implementation process took long enough to reach a critical mass that it eventually stalled. This was then amplified by the company being acquired by Fastly, stopping all progress in its tracks.

Thankfully, by going this route the partially delivered design vision didn’t leave the experience any worse than it was prior to when we were acquired and progress stopped. The design just ended up in a weird place where it was partly on the old system and partly on the new system. It was clearly still the same old ship just with maybe 50% new pieces.

Verdict: A partial success. Would still recommend if the circumstances are right. 🥲

The “land & expand” strategy

What is it?

“Land and expand” is a phrase I borrowed from SaaS sales. It describes a customer acquisition and sales growth process in which the first goal is to land a customer on a small deal. Get them in the door. Then as that customer uses your product, you build trust with them by consistently adding more value, expanding your position over time.

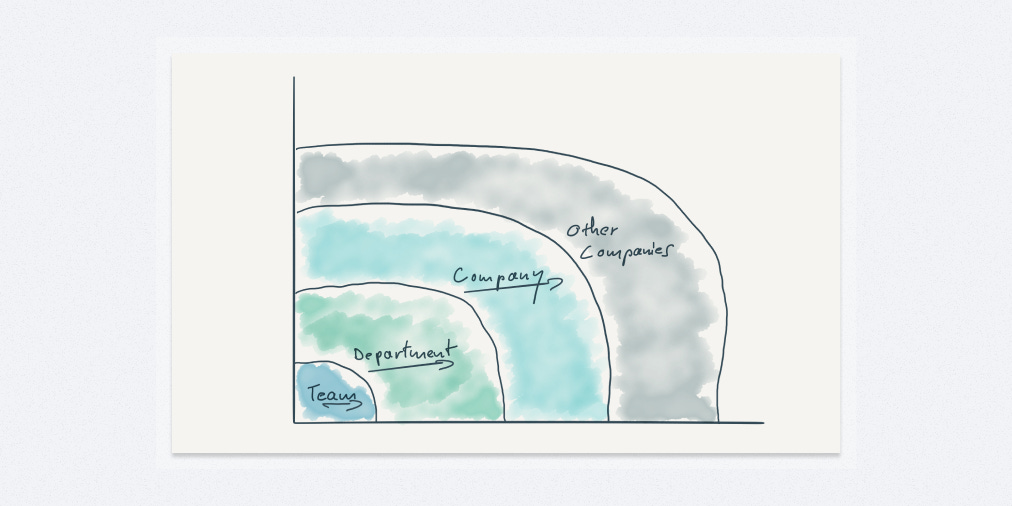

With design systems, “landing” a system looks like a very scoped down version of the “blow it up” strategy. You pick a specific, representative portion of your applications(s) to redesign. This landing spot serves as the initial testing ground and pilot program for your nascent system. Ideally it is just big enough to represent of the majority of the components and patterns that you need to start your system.

Then once you’ve done your contained “blow up” and landed the system, “expanding” looks more like the “Ship of Theseus” strategy in that it’s a gradual drive to adopt and refine the system across all corners of the platform.

What do I think about it?

I like it! For a number of reasons! 🥳

It gives designers a big enough scope of work up front to think holistically while also limiting that scope to one landing point, reducing complexity, dependencies and risk.

The landing point serves as a de facto testing ground for the system. Because no matter how well-defined a component looks in isolation, it isn’t until you put it in context that you know for sure whether or not it’s delivering.

You get both a system starter kit and a visible chunk of new feature UI that can represent it, helping you feel the momentum and build organizational support for expanding the system.

It allows most of your customer-facing feature design workflows to continue business-as-usual until the time comes for them to adopt the system.

How did it manifest in my career?

This is the strategy I adopted when I joined JupiterOne in summer 2021 and have since been implementing across our platform.

Landing

At JupiterOne we picked our Integrations feature as our system landing point. We thought it was a good candidate for two reasons:

It was already in need of work due to new constraints from the company’s growth.

It was an important feature but not the most high profile. So it had sufficient complexity to test the system but not a ton of organizational pressure to deliver anything too mind-blowing.

We stood up the very first version of our component library (which we named “Juno”) in tandem with starting work on the feature refresh. The context of the feature development informed the design of the components and the new composition of the components in turn informed the refresh of the feature.

Meanwhile the other 95% of JupiterOne continued to serve our customers in its existing form.

Expanding

As the feature and system started rounded into shape we brought a second team onboard to begin leveraging Juno components in another part of the platform with the agreement that they would be helping us test and refine.

This was the first of many expansion points.

Going forward, some sections will adopt Juno in a more incremental “Ship of Theseus” style, pulling in more targeted updates over time. Other sections will require something closer to a “blow-up” approach, but since the core system components will have already been designed and tested, the process of re-architecting will be substantially more approachable.

Verdict: So far so good. Would recommend, but will report back! 😇

In sum

Don’t “blow it up” with software unless you really have no alternative

Try to make “Ship of Theseus” style system enhancements possible, just don’t expect that approach to be the best for establishing new systems.

Aim to “land” your system with a well-scoped pilot project and then gradually “expand” it over time to the rest of your platform.

If you got a little value in this post, consider subscribing, sharing or following me on Twitter. If you got a lot of value I’d appreciate it if you bought me a coffee 😎☕️.

Well written Patrick! A lot of companies would be wise to read this and other related articles on this topic to save themselves both time and money (as well as a lot of tears). Having attempted two of these three approaches, I could not agree more that the "big bang / blow-it-up" approach will most likely fail for you every time. In truth, building the design system is in many ways easier than the process of adopting it. This is why a strategy like the "land and expand" works well as it gives you a pre-defined scope within your application that allows you to start establishing a level of trust (and communication) with the various stakeholders of the system while not being burdened with the monumental effort of having to update your entire UI at one time. I really enjoyed this post, keep up the good work!

Great post! I've also done "Land and Expand" at prior jobs and found it to be an effective approach. Like you said, it's way easier for design to move quickly with a new design system than it is for engineering/software.